Insurance Money, AI, and a Super Bowl Ad

TWG Global: the money behind the Cadillac F1 machine

⏰ Reading time: 10 minutes

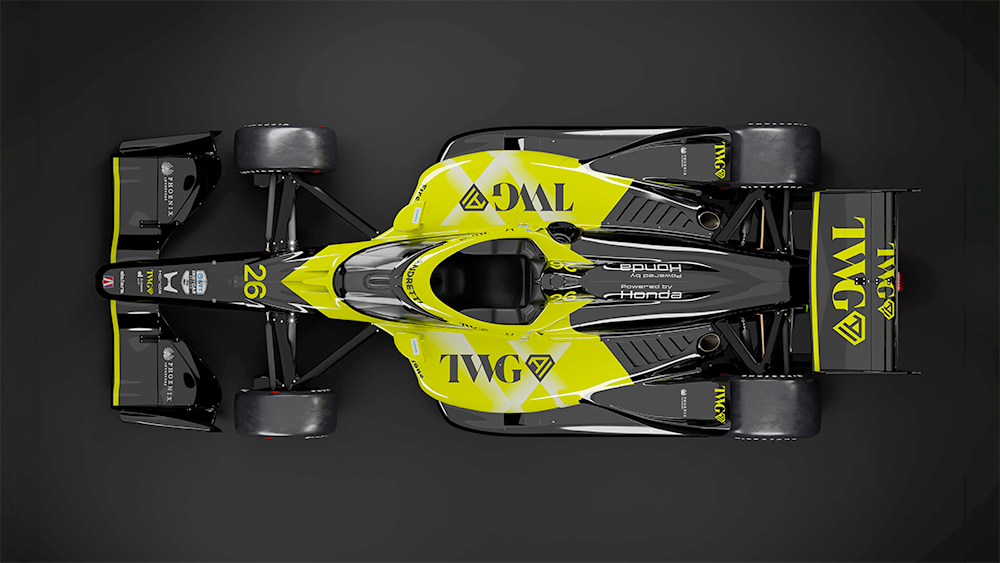

Today is the day. As you read this, a chrome-clad box in Times Square is thawing to reveal the first full Cadillac Formula 1 livery, timed to a television advertisement during Super Bowl LX. (The expected time of airing is some point around 2200 EST / 0300 GMT)

The New England Patriots and Seattle Seahawks provide the backdrop. The audience is estimated at north of 130 million American viewers. This is not how Formula 1 teams normally introduce themselves to the world.

That, of course, is the point.

The TWG Global operation behind the Cadillac F1 entry has spent the past eighteen months spending money with institutional patience and deploying it with the strategic logic of people who have built franchise value in other sports.

The Walter Empire

Mark Walter is the figure around whom TWG Global was originally built. Born in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in 1960, Walter studied business administration at Creighton University before earning a law degree at Northwestern. He never practiced law. In the mid-1990s, he co-founded Liberty Hampshire, a Chicago investment management firm, which merged into the entity that would become Guggenheim Partners. Walter co-founded Guggenheim in the late 1990s and has served as its CEO ever since. Today, Guggenheim manages assets exceeding $345 billion across its investment and securities divisions.

TWG Global exists as Walter’s personal holding company and investment vehicle, through which he consolidates an extraordinary range of interests: financial services, insurance, renewable energy, sports, media, entertainment, art, eco-tourism, and agriculture. Forbes estimates his net worth at approximately $6.1 billion. Bloomberg has pegged it somewhat higher. What matters is not the precise figure but the source. Walter’s wealth is substantially derived from the insurance and annuities business, specifically through the Group 1001 collective, which encompasses Delaware Life and other carriers. Group 1001 sits under TWG Global’s subsidiary Delaware Life Holdings and reports combined assets under management of more than $66 billion.

This is important. Walter’s business model has historically relied on capital drawn from the insurance side of his portfolio, where long-term liabilities create enormous pools of investable cash. When Guggenheim Baseball Management purchased the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2012 for $2.15 billion, Walter’s personal contribution was reported to be around $100 million. Guggenheim-related businesses supplied much of the rest. His share of the Dodgers is approximately 27 percent. This pattern, leverage, co-investment, and the patient deployment of insurance-derived capital, repeats across the portfolio.

Walter also owns or co-owns stakes in the Los Angeles Lakers (he agreed to purchase majority control from the Buss family in 2025 at a $10 billion valuation), the Los Angeles Sparks, Chelsea Football Club (through a 12.7 percent stake in the BlueCo holding company), RC Strasbourg Alsace, and the Professional Women’s Hockey League. The accumulation is not random. It is a deliberate strategy to build a diversified global sports portfolio, using those assets both for their appreciation potential and, critically, as advertising platforms for Gainbridge, the consumer-facing insurance brand within the Group 1001 family.

This makes sense because Gainbridge has been the thread connecting Walter’s sports interests to his financial services core. Gainbridge has naming rights to the Indiana Pacers and Fever arena (Gainbridge Fieldhouse), is the presenting sponsor of the Indianapolis 500, and was the primary sponsor of Colton Herta’s IndyCar entry under the Andretti banner. In this model, motorsport is not merely entertainment. It is a distribution channel for financial products.

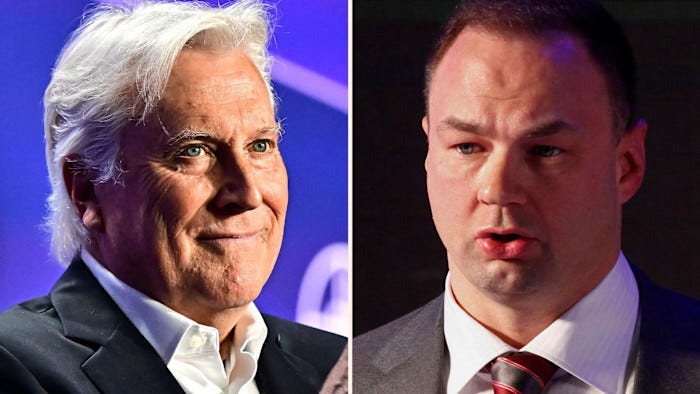

The Other Co-Chair

Thomas Tull, who became TWG Global’s co-chairman in 2025, is a different kind of billionaire. Where Walter is the quiet financial engineer, Tull is the self-described “fanboy”. He’s a film producer, technology investor, and competitive sports enthusiast from Endwell, New York. His net worth is estimated at approximately $5.3 billion.

Tull’s fortune was made primarily through Legendary Entertainment, the production company he founded in 2005, which co-financed blockbusters including The Dark Knight, Inception, Jurassic World, and The Hangover through a landmark deal with Warner Bros. In 2016, he sold Legendary to China’s Wanda Group for $3.5 billion. He subsequently founded Tulco, a Pittsburgh-based holding company focused on applying artificial intelligence and machine learning to large-industry investment decisions. Among Tulco’s notable moves was the sale of its AI insurance business to Acrisure in 2020 for $400 million.

Tull is also a minority owner of my beloved Pittsburgh Steelers and holds stakes in the New York Yankees. He sits on the board of trustees at Carnegie Mellon University and the Baseball Hall of Fame. He once attempted to buy the San Diego Padres.

When Tull merged Tulco into TWG Global, the resulting entity gained something it had lacked: a technology thesis. TWG Global is now explicitly organised around the belief that artificial intelligence can be embedded across its entire portfolio. In February 2025, TWG became a founding corporate member of MIT’s Generative AI Impact Consortium. In March 2025, it partnered with Palantir Technologies to develop commercial AI tools for financial services. By May 2025, Elon Musk’s xAI had joined that partnership. In January 2026, TWG AI was announced as the official artificial intelligence partner of Andretti Global, with primary partnerships across IndyCar and Formula E.

Whether the AI integration amounts to a genuine competitive advantage or merely clever branding remains to be seen. The word is that the Palantir-xAI collaboration focuses on processing unstructured financial data rather than directly on lap times. But the ambition is real, and the capital committed to it is substantial.

The Scale of the Operation

In April 2025, TWG Global entered a multi-billion-dollar partnership with Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund Mubadala Investment Company. Under this arrangement, Mubadala Capital anchored a $10 billion syndicated investment in TWG Global as part of a broader $15 billion equity raise. TWG, in return, committed $2.5 billion to Mubadala Capital products and acquired a strategic minority stake (5 percent) in Mubadala Capital itself. The deal valued TWG Global’s enterprise at over $40 billion.

The Towriss Trajectory

The man actually running the motorsport operation is neither Walter nor Tull. It is Dan Towriss, 53, CEO of TWG Motorsports and Group 1001 Insurance, and the individual most directly responsible for assembling the racing portfolio now under the TWG umbrella.

Towriss’s path to Formula 1 is, to put it mildly, unconventional. Born in Indiana in 1972, he attended Muncie Central High School and Indiana University on a baseball scholarship. An elbow injury ended his athletic career, and he transferred to Ball State University, where he graduated in 1994 with a degree in actuarial science. He founded Group 1001, built it into a $66 billion asset management operation, and might have spent his career entirely in insurance had it not been for a chance encounter with a young racing driver.

In 2017, IndyCar driver Zach Veach was looking for sponsorship to compete in the Indianapolis 500. Veach’s pastor connected him with Towriss, whose Gainbridge brand was seeking marketing platforms. Towriss agreed to sponsor the car. The following year, when Veach signed with Andretti Autosport, Gainbridge came along. Towriss attended his first race, fell in love with the sport, and rapidly increased his involvement.

By 2022, Towriss had become co-owner of Andretti Global, though no formal announcement was made. The transaction reportedly occurred around the time Gainbridge renewed its multi-year deal to headline the Indianapolis 500. Michael Andretti retained majority ownership, but Towriss’s capital was fuelling the organisation’s expansion into new series, new facilities, and the ambitious pursuit of a Formula 1 entry.

In October 2024, Michael Andretti stepped back from the day-to-day running of the team. The timing was not coincidental. For over a year, the Andretti F1 bid had been blocked by Formula One Management, which argued that the Andretti name did not bring sufficient value to the championship. The existing teams opposed the proposal, primarily on the grounds that it would dilute profits under the Concorde Agreement. FOM had, however, signalled that it would be more receptive to an entry fronted by General Motors and its Cadillac brand, particularly if GM committed to becoming a power unit manufacturer.

With Andretti out of the operational picture, TWG Global moved quickly. In November 2024, Walter’s holding company acquired full ownership of Andretti Global. Within weeks, the restructured entry (now branded as the Cadillac Formula 1 Team) received provisional approval from FOM. Final approval was granted in March 2025, and GM paid an expansion fee of $450 million (reportedly more than double the original ask) to secure entry. GM also committed to supplying its own power unit from the 2029 season. In the interim, Cadillac will race with Ferrari engines.

Mario Andretti, the 1978 world champion, was given a seat on the team’s board. Michael Andretti was named an advisor. Neither runs anything. The operational leadership rests with Towriss and team principal Graeme Lowdon, the former boss of the Marussia/Manor F1 operation.

A Multi-Series Approach

What makes TWG Motorsports is the breadth of its portfolio. When the division was formally launched in February 2025, it consolidated five distinct racing operations under a single corporate umbrella:

Cadillac Formula 1 Team — the new entry for 2026, partnered with General Motors, based in Fishers (Indiana), Charlotte (North Carolina), Warren (Michigan), and Silverstone (England). Ferrari-powered until 2029. Drivers: Sergio Pérez and Valtteri Bottas. Reserve: Zhou Guanyu. Test driver: Colton Herta.

Andretti Global — competing in IndyCar (three cars for Will Power, Kyle Kirkwood, and Marcus Ericsson), Indy NXT, and Formula E (with Jake Dennis and Felipe Drugovich).

Spire Motorsports — a NASCAR Cup Series and Truck Series team.

Wayne Taylor Racing — competing in IMSA’s GTP and GTD classes, as well as the Lamborghini Super Trofeo North America series. A formidable sportscar operation.

Walkinshaw TWG Racing (formerly Walkinshaw Andretti United) — a Bathurst 1000-winning outfit in Australia’s Supercars Championship, a three-way partnership between Walkinshaw Racing, TWG Motorsports, and United Autosports.

The leadership structure beneath Towriss includes Jill Gregory (COO and a veteran motorsport executive, now also serving as president of Andretti Global) and Doug Duchardt (Chief Performance Officer with two decades of experience at Hendrick Motorsports, Chip Ganassi Racing, and Spire).

The clearly stated ambition is to create a holding company that competes simultaneously across the world’s major racing championships, capturing cross-series collaborations in engineering, commercial partnerships, data analysis, and talent development.

The sports conglomerate model is not entirely new (Red Bull operates across F1, NASCAR, MotoGP, and various other disciplines through different entities), but the corporate structure here is unusually centralised. Whether that centralisation brings efficiencies or bureaucratic friction will depend on how well the Indianapolis-based leadership understands the very different cultures, regulations, and competitive dynamics of five disparate racing series.

What Does it Mean?

There are several ways to read the TWG Global story.

The optimistic reading is that this is a transformative moment for American motorsport. A credible, well-capitalised ownership group—backed by sovereign wealth fund money, staffed with experienced racing professionals, and partnered with the largest American automaker—is entering Formula 1 as a constructor for the first time since the Haas project a decade ago. The facilities are being built. The car has completed its shakedown at Silverstone. Experienced drivers have been signed. The pieces are in place.

The more cautious reading is that TWG Global is, at its core, a financial services conglomerate that views motorsport primarily as a marketing platform and an asset class. The Mubadala money provides enormous firepower, but sovereign wealth fund investors expect returns. The permanent capital structure (no fundraising cycles, no fund life constraints) gives TWG patience, but patience is not the same as passion, and Formula 1 has a long history of punishing entrants who underestimate what it takes to compete at the front.

The Cadillac F1 team will almost certainly spend its first season towards the back of the field, as every new constructor does. Lowdon has been careful to manage expectations. Bottas has talked about preparing “for the worst.” The real test will come in 2029, when GM’s own power unit is scheduled to arrive, and the team must decide whether it is content to be a midfield participant or whether it is prepared to invest at the level required to challenge for podiums and, eventually, championships.

The $450 million expansion fee, the Ferrari engine supply deal, the multi-site facility construction, and the 400-plus employees already at Silverstone. But TWG Global’s enterprise value of $40 billion makes that investment, in relative terms, a rounding error. The question is whether the people at the top have the competitive obsession that distinguishes successful F1 operations from expensive failures. The insurance industry rewards prudence and risk management. Formula 1 rewards something considerably more reckless.

For now, the car is on the grid. The Super Bowl livery launch is imminent. The money is in the bank. What happens next will determine whether TWG Motorsports becomes a permanent force in the sport or another well-funded American adventure that ends in quiet withdrawal. The history of Formula 1 suggests both outcomes are equally plausible.

A realistic first-season target is to finish P8–P10 in the constructors’ championship, avoid catastrophic reliability, and maintain sufficient operational credibility to justify the investment thesis. Finishing last would invite the narrative that TWG paid $450 million for the privilege of running at the back. Scoring points in the first five races would exceed all reasonable expectations. The truth will likely fall somewhere in between.

It worries me some of the people who are backing this TWG effort in particular those who are in partnership on the AI side of the business.

Another great post. The eternal motorsports question - where does the money come from?